Attipate Krishnaswami Ramanujan

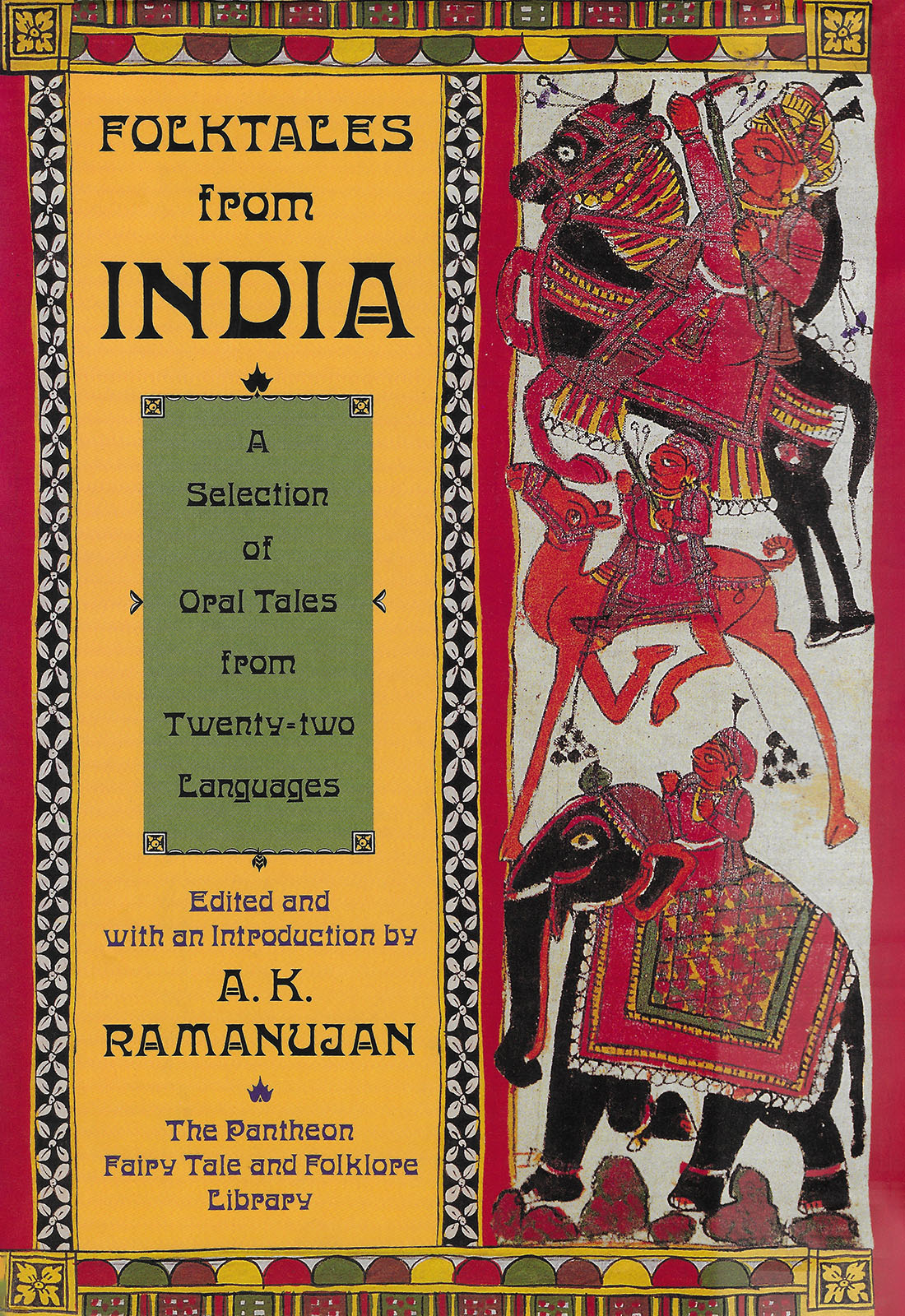

Folktales from India

Ce recueil de contes, dont voici un florilège, fut compilé par Attipate K. Ramanujan et ses proches dans toute l’Inde et traduits en anglais, puis publiés aux États-Unis où il résidait alors. Pour plus de commodité, ils sont regroupés ici par langues d’origine. La carte linguistique interactive permet de localiser celles utilisées (les 22 langues ne sont pas toutes les langues officielles).

La préface ci-dessous exprime l’état d’esprit avec lequel Ramanujan a compilé et publié ce recueil.

| Preface1 | Préface |

|---|---|

|

Attipate K. Ramanujan University of Chicago June 1991 |

Traduction : Jyoti Garin |

| This book of Indian oral tales, selected and translated from twenty-two languages, covers most of the regions of India. It is called Folktales FROM India, not OF India, for no selection can truly “represent” the multiple and changing lives of Indian tales. It presents instead examples of favourite narratives from the subcontinent. With few exceptions, each of these tales, though chosen from a teller in one language and region, is also told with variations in other regions. Every tale here is only one telling, held down in writing for the nonce till you or someone else reads it, brings it to life, and changes it by retelling it. These stories were handed down to me, and in selecting, arranging, and adapting, I’ve inevitably reworked them somewhat. So, consider me the latest teller and yourself the latest listener, who in turn will retell the tale. Like a proverb, a story gains meaning in context; in the context of this book, the meanings are made between us now. A folktale is a poetic text that carries some of its cultural contexts within it; it is also a traveling metaphor that finds a new meaning with each new telling. I have arranged the tales in cycles as I would arrange a book of poems, so that they are in dialogue with each other and together create a world through point and counterpoint. | Ce recueil de contes oraux indiens, sélectionnés et traduits depuis vingt-deux langues, couvre la plupart des régions de l’Inde. Il s’intitule Contes populaires de l’Inde, et non Contes populaires indiens, car aucune sélection ne peut véritablement « représenter » la vie multiple et changeante des contes indiens. Il s’agit plutôt de récits bien connus du sous-continent. À quelques exceptions près, chacun de ces contes, raconté par un conteur dans une langue et une région données, peut aussi se retrouver avec des variantes dans d’autres régions. Chaque conte, raconté d’une certaine manière et consigné par écrit pour un instant, reprend vie lorsque vous ou quelqu’un d’autre le lisez, le modifiant dans votre propre narration. Ces histoires m’ont été transmises et, en les sélectionnant, en les arrangeant et en les adaptant, je les ai inévitablement quelque peu retravaillées. Considérez-moi donc comme le dernier conteur et vous-même comme le dernier auditeur, qui à son tour racontera l’histoire. Comme un proverbe, une histoire prend sens dans son contexte ; sa signification est donc liée à ce livre et prend son sens entre nous. Un conte populaire est un texte poétique qui porte en lui certains de ses contextes culturels ; c’est aussi une métaphore voyageuse qui trouve un nouveau sens à chaque nouveau récit. J’ai organisé les contes en cycles comme je l’aurais fait pour un livre de poèmes, afin qu’ils dialoguent les uns avec les autres et créent ensemble un monde par le point et le contre-point. |

| Nothing can reproduce the original telling of a tale. These were all translated by different hands at different times and places, and I have retold them – making slight changes in some, and more than slight changes in others where the language was fulsome, cumbersome, or simply outdated. I have kept close to the narrative line, omitted no detail or motif, and tried to keep the design of the plot intact. I have not mixed episodes from different variants to make them more dramatic or artistic than they already are. | Rien ne peut reproduire le récit original d’un conte. Ceux-ci ont tous été traduits par des mains différentes à des moments et à des endroits différents, et je les ai racontés – en apportant de légers changements pour certains, et des changements plus substantiels pour d’autres où la langue était complète, lourde ou simplement dépassée. Je suis resté proche de la ligne narrative, n’ai omis aucun détail ni motif, et j’ai essayé de garder intacte la conception de l’intrigue. Je n’ai pas ajouté des épisodes d’autres variantes pour ne pas altérer leur dramaturgie ou leur beauté. |

| I have taken care to include only tales from actual tellers, rather than literary texts. About a quarter of these tales were personally collected or recollected; some have never been published before, certainly not in an English translation. Many of the others were chosen from late-nineteenth-century sources: some of the finest oral folktale collections were compiled then, and published in journals like The Indian Antiquary, The Journal the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, and North Indian Notes and Queries. Civil servants, their wives and daughters, foreign missionaries, as well as many Indian scholars, took part in this enterprise. Indeed, more than two thousand tales were collected, translated, and published during this time; they are old, yet are told and retold today. | J’ai pris soin de n’inclure que des contes de conteurs authentiques, délaissant les textes littéraires. J’ai personnellement recueilli ou me suis remémoré environ un quart d’entre eux ; certains n’ont jamais été publiés auparavant, a fortiori dans une traduction anglaise. Beaucoup d’autres ont été choisis à partir de sources datant de la fin du xixe siècle : c’est à cette époque en effet que certaines des plus belles collections de contes folkloriques oraux ont alors été compilées et publiées dans des revues comme The Indian Antiquary, The Journal the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal et North Indian Notes and Queries. Des fonctionnaires, leurs femmes et leurs filles, des missionnaires étrangers, ainsi que de nombreux savants indiens ont contribué à cette entreprise. C’est ainsi que plus de deux mille contes ont pu être recueillis, traduits et publiés pendant cette période ; ils sont anciens, mais sont toujours et encore racontés aujourd’hui. |

| While the Introduction discusses the importance of oral traditions for any study of India, one should bear in mind that these tales are meant to be read for pleasure first, to be experienced as aesthetic objects. As an old Chinese proverb tells us: “Birds do not sing because they have answers; birds sing because they have songs.” The songs of course have territories, species, contexts, and functions. | Alors que l’introduction traite de l’importance des traditions orales pour toute étude de l’Inde, il faut garder à l’esprit que ces contes sont d’abord destinés à être lus pour le plaisir, à être vécus comme des objets esthétiques. Comme le dit un vieux proverbe chinois : « Les oiseaux ne chantent pas parce qu’ils ont des réponses ; les oiseaux chantent parce qu’ils ont des chants. » Les chants ont bien sûr des territoires, des espèces, des contextes et des fonctions. |

| In making this book, not only am I indebted to countless tellers all over India – beginning with my own grandmother – but to collectors, scholars, editors, and index makers from different parts of the world for over a century. Wendy Wolf initiated this project through Susan Bergholz five years ago; Barbara Stoler Miller’s and Wendy Doniger’s delight in the tales has been an inspiration; Yoji Yamaguchi’s courtesy, editorial skills, and gentle reminders have helped me finish and shape the book. I heard and collected folktales long before I thought about books: meeting Edwin Kirkland in 1956 in a small South Indian town made me aware of folklore as a field. Half a lifetime of friendship with Carolyn and Alan Dundes (whom I met the very first month after I arrived in America) has been a continuous pleasure and a continuing education. Colleagues in the Department of South Asian Languages at the University of Chicago, grants from the American Institute of Indian Studies, and the riches of the Regenstein Library have all contributed towards this book. I thank them all. | En réalisant ce livre, je suis non seulement redevable à d’innombrables conteurs dans toute l’Inde – à commencer par ma propre grand-mère – mais aussi à des collectionneurs, des universitaires, des éditeurs et des compilateurs de différentes parties du monde depuis plus d’un siècle. Wendy Wolf a initié ce projet par l’intermédiaire de Susan Bergholz il y a cinq ans ; le plaisir de Barbara Stoler Miller et Wendy Doniger dans les contes a été une source d’inspiration ; la courtoisie, les compétences éditoriales et les gentils rappels de Yoji Yamaguchi m’ont aidé à terminer et à façonner le livre. J’ai entendu et collectionné des contes populaires bien avant de penser à les rassembler dans un livre : la rencontre d’Edwin Kirkland en 1956 dans une petite ville du sud de l’Inde m’a fait prendre conscience du folklore en tant que domaine. Une demi-vie d’amitié avec Carolyn et Alan Dundes (que j’ai rencontrés le tout premier mois après mon arrivée en Amérique) a été un plaisir ininterrompu et une formation continue. Des collègues du Département des langues sud-asiatiques de l’Université de Chicago, des bourses de l’American Institute of Indian Studies et les trésors de la bibliothèque Regenstein ont contribué à ce livre. Je les remercie tous. |

| 1 | Voir une analyse de cette œuvre dans l’article du Dr. Kavita S. Kusugal : “Indian Folktales: Ramanujan’s Interpretation” (2014). |

| Gopal Bhar the star-counter | Gopal Bhar, le compteur d’étoiles |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| One day, the Nawab sent word to Maharaja Krishnachandra that he wanted the whole earth measured, from side to side and from end to end, and that he would greatly appreciate it if the Maharaja would take it upon himself to count the stars in the sky as well. The Maharaja was astounded and said, “I don’t want to seem uncooperative, but you have commanded me to do the impossible.” | Un jour, le Nabab fit part au Maharajah Krishnachandra de son souhait que la terre entière soit mesurée, de long en large et de haut en bas, et qu’il apprécierait grandement que le Maharajah prenne sur lui de compter également les étoiles dans le ciel. Le Maharajah fut stupéfait et dit : « Je ne veux pas faire preuve de mauvaise volonté, mais vous exigez de moi l’impossible. » |

| And the Nawab said, “But do it you will.” | Le Nabab lui répondit : « Tu vas pourtant devoir le faire. » |

| So the Maharaja fell into a brown study and brooded over how he might fulfil the demands of the Nawab. | Alors le Maharajah sombra dans une profonde réflexion et réfléchit à la manière de répondre aux exigences du Nabab. |

| It was not long before Gopal Bhar passed by, and seeing the Maharaja in such a state of despair, he tugged gently at the ends of his moustache and said, “Maharaj, what is this I see? If you have troubles, you need only tell your Gopal, and all will be well.” | C’est à ce moment que Gopal Bhar vint à passer et, voyant le Maharajah plongé dans une telle désespérance, il tira doucement les pointes de sa moustache et lui dit : « Maharajah, dites-moi, si vous avez des soucis, faites-en part à votre serviteur Gopal, et tout rentrera dans l’ordre. » |

| The king was not so easily consoled. He said, “No, Gopal, this is a problem even you cannot solve. The Nawab has commanded me to measure the earth, from side to side and from end to end. And as if that were not enough, he wants me to count the stars in the sky as well.” | Le roi, inconsolable, lui répondit : « Non, Gopal, c’est un problème que même toi ne sauras résoudre. Le Nabab m’a demandé de mesurer la terre, de long en large et de haut en bas. Et comme si cela ne suffisait pas, il veut que je compte aussi les étoiles dans le ciel. » |

| Gopal was not dismayed. He said, “Ha, Maharaj, nothing could be easier. Appoint me your official Earth-Measurer and Star-Counter, and set your mind at rest. And when I am through, I shall myself go to the Nawab with the results. Only one favour: ask the Nawab for one year to finish the job and a million rupees for operating expenses. In one year’s time, I’ll bring him the results.” | Gopal ne se désarçonna pas : « Eh bien, Maharajah, rien de plus facile ! Nommez-moi votre arpenteur de la terre et compteur d’étoiles attitré, et reposez-vous sur moi. Et quand j’en aurai fini, je remettrai personnellement les résultats au Nabab. J’ai cependant une requête : demandez au Nabab un délai d’un an pour accomplir cette tâche et un million de roupies pour les faux frais. Et dans un an, je lui apporterai les résultats. » |

| The Maharaja was greatly pleased and relieved, since if the job were not done it would be Gopal’s head that would come off and not his own. He did as Gopal had asked. | Le Maharajah fut pleinement satisfait et soulagé, car, si le travail n’était pas réalisé, c’est Gopal qui serait décapité et non lui. Il fit donc ce que Gopal lui avait demandé. |

| So Gopal passed a very pleasant year, spending the million rupees on the most delightful women and the most delicious food in the kingdom, as well as on palaces and elephants and jewels and other things of that type. He spent, in fact, such a pleasant year that at its end he went to the Maharaja again, jingling the four nickel coins and two coppers that remained of the million rupees, and assuming a worried frown, said, “Maharaj, the task is more difficult than I had anticipated. I’ve made an excellent start, and the results are promising. But I’ll need another year’s time. And incidentally, another million rupees. Operating expenses.” | Ainsi Gopal passa-t-il une année très agréable, dilapidant ce million de roupies en jouissant des femmes les plus ravissantes et des mets les plus délicieux du royaume, ainsi qu’en palais, éléphants, bijoux et autres divertissements du même acabit. En fait, il passa une année si agréable qu’à la fin, il revint chez le Maharajah en ne faisant plus tinter que quatre pièces de nickel et deux de cuivre, vestiges du million de roupies, et l’air penaud, bredouilla : « Ah Maharajah, cette tâche s’est avérée plus ardue que je ne l’avais anticipée. Après un excellent départ et des résultats prometteurs, il va me falloir une année supplémentaire. Et incidemment, un autre million de roupies : frais de fonctionnement, vous comprenez… » |

| The Maharaja reluctantly petitioned the Nawab, and the Nawab reluctantly granted the extra year and the second million rupees. And Gopal passed his year even more pleasantly than the first, since now he had some experience in these matters. | À contrecœur, le Maharajah en fit la requête auprès du Nabab, qui, à contrecœur lui aussi, accorda l’année supplémentaire et le deuxième million de roupies. Et Gopal passa cette année encore plus agréablement que la première, ayant acquis une certaine expérience en la matière. |

| Exactly one year later to the hour, Gopal came dragging himself up the road to the Nawab’s palace. With him were fifteen bullock carts, crammed to creaking with the finest thread, tangled and jumbled and matted and flattened down, and five very fat woolly sheep. He led this odd procession through the gates of the palace and into the court of the Nawab, made a deep and graceful bow, and said, “Excellency, it has been done as you ordered. I have measured the earth from end to end and from side to side, and I have counted the stars in the sky.” | Un an plus tard, à l’heure dite, Gopal revint, se traînant jusqu’au palais du Nabab. Escorté par quinze chars à bœufs, bourrés jusqu’à craquer avec le fil le plus fin, emmêlé, tressé et aplati, et cinq moutons laineux bien gras. Il conduisit cet équipage insolite jusqu’aux portes du palais et traversa la cour du Nabab, à qui il fit une profonde et gracieuse révérence, puis proclama : « Excellence, vos ordres ont été exécutés à la lettre. J’ai mesuré la terre de droite à gauche et de haut en bas, et j’ai compté les étoiles dans le ciel. » |

| “Excellent. And now give me the figures. The exact figures.” | « Parfait ! Eh bien donne-moi les résultats. Je veux des chiffres précis. » |

| “Figures, Majesty? Figures were not in the agreement. I’ve done as you have commanded. The earth is as wide as the thread in the first seven bullock carts is long, and it is as long as the thread in the other eight is long. There are, furthermore, just as many stars in the sky as there are hairs on these five sheep. It took me a long time to find sheep with just the right number of hairs.” | « Les chiffres, Majesté ? Mais les chiffres ne figuraient pas dans votre demande. J’ai exécuté scrupuleusement celle-ci. La terre a la même largeur que la longueur du fil des sept premiers chars à bœufs, et la même hauteur que celle du fil dans les huit autres chars. En outre, il y a autant d’étoiles dans le ciel que de poils sur ces cinq moutons. Il me fut très difficile de trouver des moutons avec le nombre exact de poils. » |

| The Nawab could only say, “Impossible! I cannot measure that thread or count those hairs. Still, you have lived up to your end of the bargain. Here’s your reward: a million rupees.” | Le Nabab ne put que lui répondre : « Mais c’est impossible ! Je ne peux pas mesurer ce fil ou compter ces poils ! Pourtant tu as respecté ta part du marché. Voici donc ta récompense : un million de roupies. » |

| And Gopal lived in ease for some little time. | Gopal put ainsi vivre dans l’opulence encore quelque temps. |

| The Brahman Who Swallowed a God | Le Brahmane qui avala un dieu |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| Bidhata, the god who writes his or her future on everyone’s forehead at birth, had doomed a poor Brahman to a peculiar fate. This Brahman was fated never to eat to his heart’s content. When he had eaten half his rice, something or other always occurred to interrupt him, so that he could eat no more. | Bidhata1, le dieu qui grave le chemin de vie sur le front de chacun le jour de sa naissance, avait condamné un pauvre brahmane2 à un bien étrange destin. Ce brahmane était contraint en effet à ne jamais manger tout son soûl. Quand il avait avalé la moitié de son riz, un événement impromptu se produisait systématiquement, interrompant son repas, de sorte qu’il ne pouvait plus terminer celui-ci. |

| One day he received an invitation to the raja’s house. He was delighted and said to his wife, “Half my rice is all I can ever eat. Never once in my whole life has my hunger been satisfied. Today I’ve by some good luck received this invitation to the raja’s house. But how am I to go? My clothes are torn and dirty, and if I go like this, most likely the gatekeeper will tum me away.” His wife said, “I’ll repair and clean your clothes. Then you can go.” And when she had provided him with decent clothes, he set out for the raja’s house. | Un jour, il reçut une invitation pour se rendre à la demeure du rajah. Enchanté, il dit à sa femme : « La moitié de mon riz, c’est tout ce que je n’ai jamais pu ingurgiter. Jamais une seule fois de toute ma vie, ma faim n’a pu être assouvie. Aujourd’hui, par chance, j’ai reçu cette invitation à la résidence du rajah. Mais comment m’y prendre ? Mes vêtements sont déchirés et sales et, si je m’y rends ainsi vêtu, il est fort probable que le gardien me refoulera. » Sa femme lui répondit : « Je vais raccommoder et nettoyer tes vêtements. Alors tu pourras y aller. » Quand elle lui eut fourni des vêtements convenables, il partit chez le rajah. |

| There, though he was late and it was evening, he was royally received. As he viewed the dishes spread out before him, the old Brahman was delighted. He thought, “Whatever happens, today I’ll eat my fill.” He then sat down and began eating. Now, it happened that a little earthen pot was hanging from a beam of the roof. Just as the Brahman had half finished his dinner, the pot broke and the pieces fell into his food. He immediately stopped eating, took his ritual sip of water to close the meal, got up, washed his hands and mouth, and went to the raja. The raja welcomed him respectfully and asked, “Thakur, are you fully satisfied?” The Brahman answered, “Maharaj, your servants were very good to me and served me all I wanted. My own fate is to blame that I couldn’t eat my fill.” “Why?” said the raja. “What happened?” “Maharaj, while I was eating, a little earthen pot fell from the ceiling and spoiled my rice,” said the Brahman. The raja was very angry when he heard this and gave his servants a scolding. Then he said to the Brahman, “Sir, you stay with me tonight. Tomorrow, I’ll have fresh food made and serve it to you with my own hands.” So the Brahman stayed in the raja’s house that night. | Là, bien que la nuit fût tombée, on le reçut royalement. À la vue des mets disposés devant lui, le vieux brahmane fut enchanté. Il pensa : « Quoi qu’il arrive, je vais enfin manger à ma faim aujourd’hui. » Il s’assit alors et entama son repas. Or, il se trouva qu’un petit pot de terre était suspendu à une poutre du toit. Au moment précis où le brahmane était au milieu de son dîner, le pot se brisa et les morceaux atterrirent dans sa nourriture. Il s’arrêta immédiatement de manger, avala sa gorgée d’eau rituelle pour clore le repas, se leva, se lava les mains et la bouche, et se rendit chez le rajah. Celui-ci l’accueillit respectueusement et lui demanda : « Thakur3, êtes-vous pleinement satisfait ? » Le brahmane répondit : « Maharaj, vos serviteurs ont été très gentils avec moi et m’ont servi tout ce que je désirais. Mais mon propre destin me condamne à ne pouvoir manger tout mon content. » « Pourquoi donc ? », demanda le rajah. « Que s’est-il passé ? » « Maharaj, pendant que je mangeais, un petit pot de terre est tombé du plafond et a gâté mon riz », dit le brahmane. À ces mots, le rajah se mit en colère et réprimanda ses serviteurs. Puis il s’adressa au brahmane : « Ô brâhmane, reste avec nous ce soir. Demain, je ferai préparer de la nourriture fraîche et je te la servirai de mes propres mains. » Ainsi, le brahmane passa-t-il la nuit chez son hôte. |

| Next day, the raja supervised the cooking himself, even prepared some of the dishes with his own hands and served the Brahman. In the great room where he was served, there was nothing that could spoil the meal. The Brahman looked around, rejoiced at the raja’s hospitality, and sat down to eat. But when he was halfway through his dinner, Bidhata saw that he must be stopped, and yet he could not see any way of doing it. So he himself took the form of a golden frog, came to the edge of the Brahman’s plantain leaf, and tumbled into his food. | Le lendemain, le rajah supervisa lui-même la préparation du repas, allant même jusqu’à confectionner certains des plats de ses propres mains avant de servir le brahmane. Le service se fit dans la grande salle. Il n’y avait rien qui pût gâcher le repas. Le brahmane jeta un coup d’œil autour de lui, se réjouit de l’hospitalité du rajah et s’assit pour manger. Mais au beau milieu du dîner, Bidhata se rendit compte qu’il fallait l’interrompre, sans pourtant trouver aucun moyen de le faire. Aussi se transforma-t-il en une grenouille dorée, s’approcha du bord de la feuille de plantain du brahmane et culbuta dans sa nourriture. |

| The Brahman was too busy to notice anything. He ate up his rice, frog and all. Dinner over, the raja asked him, “How is it now, thakur? Were you satisfied today?” The Brahman answered, “Maharaj, I’ve never dined so well in all my life.” Saying this, he took his leave, received gifts and money from the good raja, and set off for home. | Le brahmane, trop occupé, ne remarqua rien. Il avala riz, grenouille et tout le reste. Le dîner terminé, le rajah lui demanda : « Alors, Thakur, êtes-vous satisfait aujourd’hui ? » Le brahmane répondit : « Maharaj, je n’ai jamais aussi bien dîné de toute ma vie. » En disant cela, il prit congé, reçut présents et argent du bon rajah, et s’en retourna chez lui. |

| That evening on his way home, while he was walking through a jungle, he suddenly heard a voice: “Brahman, let me go! Brahman, let me go!” The Brahman looked all around him, but he could see nobody. Again he heard the voice: “Brahman, let me go!” Then he said, “Who are you?” The answer came: “I’m Bidhata, I’m Bidhata!” The Brahman asked again, “Where are you?” Bidhata answered, “Inside your stomach. You’ve swallowed me.” “Impossible!” said the Brahman. “Yes,” said Bidhata, “in the form of a frog, I tumbled into your food, and you ate me up.” “Ah, nothing could be better,” replied the Brahman. “You’ve bothered me all my life, you rascal. I won’t let you go! I’ll rather close up my throat.” Bidhata, in great fear, said again, “Brahman, let me go! I’m stifled in here!” But the Brahman hurried home quickly, and when he arrived, said to his wife, “Give me a hookah, and you hold a stick ready in your hand.” His wife did so at once, and the Brahman at down and smoked the hookah for a long time contentedly, taking great care not to set Bidhata free. The god was further stifled by the smoke, but the Brahman quite ignored all his cries for help. | Chemin faisant, alors qu’il traversait la jungle, il entendit soudain une voix : « Brahmane, laisse-moi sortir ! Ô Brahmane, laisse-moi partir ! » Le brahmane regarda tout autour de lui, mais il ne vit personne. À nouveau la voix l’enjoignit : « Brahmane, laisse-moi sortir ! » Puis il dit : « Qui es-tu ? » La réponse ne tarda pas : « Je suis Bidhata, je suis Bidhata! » Le brahmane demanda encore : « Où es-tu ? » Bidhata répondit : « À l’intérieur de ton estomac. Tu m’as avalé. » « Impossible ! » rétorqua le Brahmane. « Si », poursuivit Bidhata, « sous la forme d’une grenouille, j’ai dégringolé dans ton plat, et tu m’as avalé. » « Eh bien c’est merveilleux ! Rien de mieux ne pouvait m’arriver ! », répondit le brahmane. « Tu m’as embêté toute ma vie, espèce de coquin. Je ne te laisserai pas sortir ! J’aimerais plutôt me boucher la gorge ! » Bidhata, très effrayé, reprit : « Brahmane, laisse-moi sortir ! J’ étouffe ici ! » Mais le brahmane se hâta de regagner son logis, et quand il arriva, il demanda à sa femme : « Apporte-moi un narguilé, et arme-toi d’un bâton. » C’est ce qu’elle fit sur-le-champ, et le brahmane s’installa et fuma le narguilé pendant un long moment avec béatitude, prenant garde à ne pas libérer Bidhata. La fumée étouffait le dieu de plus en plus, mais le brahmane resta de marbre devant ses cris d’appel au secours. |

| Meanwhile, there was a terrible commotion in the three worlds. Without Bidhata to regulate matters, the universe was on the verge of a collapse. Then the gods assembled in council decided that one of them must be sent to the Brahman. But who? They all agreed that the goddess Lakshmi would be the right one to go. She said, “If I go to that Brahman, I shall never come back.” But they all prayed and begged, so she agreed and went to the Brahman’s house. When the Brahman learned that it was Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and fortune, at his door, he put his upper cloth around his neck as a mark of respect, gave her a seat, and asked her what, in the name of wonder, had brought her to a poor man’s house. “Thakur,” said the goddess, “you’ve taken Bidhata a prisoner. Let him go, or the universe will be ruined.” “Give me the stick,” said the Brahman to his wife, “and I’ll show you what I think of this goddess of good fortune. From the day I was born, she has shunned me, I’ve had nothing but bad luck, and here she comes to my house, this Lakshmi!” When she heard this, the goddess vanished, trembling with fear. No one had ever talked to her like that before in all the ages. She told the gods what had happened, and, after another huddle, the gods sent Saraswati, the goddess of learning. | Pendant ce temps, une sourde agitation gagna le royaume des trois mondes. Sans Bidhata comme élément régulateur, l’univers menaçait de d’effondrer. Alors les dieux, réunis en conseil, décidèrent d’envoyer l’un des leurs auprès du brahmane. Mais qui ? Tous tombèrent d’accord pour considérer que la déesse Lakshmi serait taillée pour cette mission. Elle refusa d’abord : « Si je vais auprès de ce brahmane, je ne reviendrai jamais. » Mais, à forces de prières, elle finit par accepter et se rendit chez lui. Lorsque le brahmane comprit que Lakshmi, la déesse de la richesse et de la fortune, était à sa porte, il orna son cou de l’étole sacrée en signe de respect, lui offrit un siège et lui demanda quel miracle l’avait conduite jusqu’à la maison d’un pauvre homme. « Thakur, dit la déesse, tu as emprisonné Bidhata. Laisse-le partir, sinon l’univers sera détruit. » « Passe-moi le bâton », ordonna le brahmane à sa femme, « et je vais te montrer ce que je pense de cette déesse de la fortune ! Depuis le jour de ma naissance, elle m’a rejeté ; je n’ai eu que malchance, et voilà cette impudente de Laxmi qui ose venir chez moi ! ». À ces mots, la déesse s’évapora, toute tremblante de peur. De tous temps, personne ne lui avait jamais parlé ainsi. Elle raconta aux dieux ce qui s’était passé, et, après une nouvelle séance secrète, les dieux envoyèrent Sarasvati, la déesse de la connaissance. |

| When Saraswati reached his house and called out, “Brahman, are you in? Brahman, are you in?” the Brahman saluted her with great respect and said, “Mother, great goddess, what do you want in a poor man’s house?” “Thakur, the universe is fast coming apart. Let Bidhata go.” The Brahman burst into a great rage and cried, “Wife, give me the stick! I’ll teach this goddess of learning. She didn’t give me even the first letters of the alphabet. Saraswati comes to my house now, does she?” Hearing this, the goddess got up in a hurry and fled, stumbling. | Quand Sarasvati arriva chez le brahmane et l’interpella : « Brahmane, es-tu là ? Brahmane, tu es là ? », le brahmane la salua avec un profond respect et déclara : « Ô Mère, grande déesse, qu’espérez-vous dans le logis d’un pauvre homme ? » « Thakur, l’univers se désintègre rapidement. Laisse sortir Bidhata ! » Le brahmane entra dans une rage folle et cria : « Femme, passe-moi le bâton ! Je vais donner une bonne leçon à cette déesse de la connaissance. Elle ne m’a même pas enseigné les premiers rudiments de l’alphabet. Et la voilà, Sarasvati, qui déboule chez moi maintenant ! » En entendant ces mots, la déesse se leva précipitamment et déguerpit en trébuchant. |

| Finally, the great god Siva himself undertook the mission. Now the Brahman was a Saiva, a devout worshipper of Siva, so devout that he would not even touch water without doing puja to Siva. Therefore, as soon as the god came, he and his wife gave him water to wash his feet, offered him bel leaves, holy grass, flowers, rice, and sandalwood, and did puja to him. Siva then sat down and said to the Brahman, “Brahman, let Bidhata go.” The Brahman said, “As you have come personally, o great Siva, of course I must let him go. But what am I to do? I’ve suffered hardships from the day I was born, thanks to this Bidhata. He is the cause of it all.” Then the great god said, “Do not trouble yourself. I’ll take you, body and soul, to heaven.” When he heard that, the Brahman relaxed his throat and opened his mouth, and Bidhata jumped out. Then Siva took the Brahman and his wife with him to his special heaven. | Finalement, ce fut le grand dieu Shiva en personne qui se chargea de la mission. Le brahmane était un shaiva, un fervent adorateur de Shiva, si dévot qu’il allait jusqu’à ne pas toucher l’eau sans faire la puja4 à Shiva. Ainsi, dès que le dieu se présenta, lui et sa femme préparèrent de l’eau pour lui laver les pieds, des feuilles de bel5, de l’herbe sacrée, des fleurs, du riz et du bois de santal, et accomplirent le rite sacré. Shiva s’assit alors et dit au brahmane : « Ô brahmane, libère Bidhata ! » Le brahmane répondit : « Comme vous êtes venu en personne, ô grand Shiva, je vais bien sûr le laisser partir. Mais que faire ? J’ai enduré des pires épreuves depuis le jour de ma naissance, à cause de ce Bidhata de malheur. C’est lui l’origine de tout cela ! » Alors le grand dieu le consola : « Ne t’inquiète pas, je t’emmènerai, corps et âme, au paradis. » À cette promesse, le brahmane relâcha les muscles de sa gorge et ouvrit la bouche. Bidhata sortit d’un bond. Alors Shiva emmena le brahmane et sa femme avec lui dans son paradis spécial. |

| 1 | Plus souvent écrit Vidhata (विधातृ), c’est le nom propre du « Dispensateur », épithète de Brahmā « l’Ordonnateur du Monde », personnifiant la Destinée avec son épouse Āyati. |

| 2 | Membre de la caste sacerdotale, la première des grandes castes traditionnelles de l’Inde. |

| 3 | Adresse respectueuse, issue d’un titre de noblesse signifiant « seigneur ». |

| 4 | पूजा pūjā : rite religieux journalier, service divin. Le rite de la pūjā a progressivement supplanté les rites solennels du sacrifice védique. |

| 5 | बिल्व bilva : Ægle marmelos, arbre de Bæl ou cognassier du Bengale ; arbre sacré dont les feuilles trilobées [tryambaka] servent d'offrande à Śiva. |

| The Barber and the Brahman Demon | Le barbier et le démon-brahmane |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| In the district of Burdwan, there lived a barber who was very idle. He would do no work and devoted his time to preening himself with an old mirror and a broken comb. His old mother rebuked him all day for this, but it didn’t touch him. At last, one day in a fit of anger, she struck him with her broom. The young barber felt humiliated by this and left home, determined never to return till he had amassed some wealth. He walked far till he reached a forest and thought of praying to the gods for help. But as he entered the forest, he met with a brahmarakshasa, a demon who was once a Brahman, dancing wildly. He was terrified but he kept his wits about him. So he mustered all his courage and began to dance too, keeping time with the demon. After a while, he asked the demon, “Why are you dancing? What has made you so happy?” | Dans la région de Burdwan1, vivait un barbier particulièrement oisif. Il ne voulait pas travailler et, armé d’un vieux miroir et un peigne cassé, il se pavanait toute la journée. Sa vieille mère l’en réprimandait à longueur de journée, mais il n’en avait cure. Enfin, un jour, dans un accès de colère, elle le frappa de son balai. Humilié, le jeune barbier quitta la maison, décidé à ne revenir que les poches cousues d’or. Il marcha longtemps jusqu’à la lisière d’une forêt et songea à implorer le secours des dieux. Mais comme il pénétrait dans la forêt, il tomba nez à nez sur un brahma-rakshasa2, un démon jadis brahmane, qui dansait tel un sauvage. Bien que terrifié, il conserva la tête froide. Aussi, rassemblant tout son courage, il entra dans la danse du démon, suivant son rythme. Puis, après quelque temps, il lui demanda : « Pourquoi danses-tu ? Qu’est-ce qui te rend si heureux ? » |

| The demon laughed and said, “I was waiting for your question because I knew you were a fool and didn’t know the reason. It’s simply because I want to feast on your delicate flesh. That’s why. Now tell me, why are you dancing?” | Le démon s’esclaffa : « J’attendais ta question sachant que tu étais stupide et que, par conséquent, tu ne connaissais pas la raison de ma danse. C’est tout simplement parce que je veux me régaler de ta chair délicate. Voilà pourquoi. Maintenant, dis-moi pourquoi, toi, danses-tu ? » |

| “I have a far better reason,” returned the barber. “Our king’s son is very ill. The doctors have recommended for his cure the heart’s blood of one hundred and one brahmarakshasas. His Majesty has proclaimed by beat of drum that he’ll give away half his kingdom and one of his beautiful daughters to anyone who gets the medicine. I have, with great trouble, captured one hundred brahmarakshasas and now, with you, I make up the full quota of one hundred and one. I have already seized your soul, and you are in my pocket.” So saying, he took out his pocket mirror and held it before the brahmarakshasa’s eyes. The terrified demon found his image in the glass. He could see it there in the clear moonlight and thought himself actually captured. He trembled and prayed to the barber to release him. The barber would not agree at first, but the demon promised him wealth worth the ransom of seven kings. Pretending to yield unwillingly, the barber said, “But where is this wealth you promise, and who will carry it and me to my house at this hour in the dead of night?” | « J’ai une bien meilleure raison », rétorqua le barbier. Le fils de notre roi est très malade. Les médecins ont prescrit, pour sa guérison, le sang du cœur de cent un brahma-rakshasa. Son Altesse a proclamé, au son du tambour, qu’il ferait don de la moitié de son royaume et d’une de ses magnifiques filles à quiconque apporterait le remède. J’ai, avec bien du mal, capturé cent brahma-rakshasa, et maintenant, avec toi, j’atteins le quota complet de cent un. J’ai déjà pris possession de ton âme et tu es dans ma poche. » Sur ces paroles, il sortit son miroir de poche et le tendit sous les yeux du brahma-rakshasa. Épouvanté, le démon vit son reflet dans la glace. Il le découvrait là, à la pâle lueur de la lune, et se crut bel et bien capturé. Il tremblait tout en implorant le barbier de le libérer. Ce dernier refusa tout d’abord, mais le démon lui promit une richesse équivalente à la rançon de sept rois. Feignant de céder à contrecœur, le barbier déclara, « Mais où se trouve donc cette richesse que tu me promets ? Et qui la transportera, avec moi, jusqu’à ma demeure au beau milieu de la nuit ? » |

| “The treasure is under that tree behind you,” said the brahmarakshasa. “I’ll show it to you and I’ll carry you with it to your house in an instant. As you know, we demons, we have special powers.” | « Le trésor se cache sous cet arbre derrière toi », dit le brahma-rakshasa. « Je vais te le montrer et je te transporterai avec lui, chez toi, en un clin d’œil. Comme tu le sais, nous autres démons, sommes dotés de pouvoirs surnaturels. » |

| Saying this, he uprooted the tree and brought out seven golden jars full of precious stones. The barber was dazzled by all that wealth, but he cunningly concealed his true feelings and boldly ordered the demon to carry the jars and himself at once to his house. The demon obeyed, and the barber was carried home with all the wealth. The demon then begged for his release, but the barber didn’t wish to part with his services so soon. So he asked him to cut the paddy of his field and bring the crop home. The poor demon believed himself still in the barber’s clutches and so consented to reap the grain. | Tout en disant cela, il déracina l’arbre et mit au jour sept jarres dorées remplies de pierres précieuses. Le barbier fut ébloui par toute cette richesse, mais, avec ruse, il dissimula son véritable sentiment. Avec audace, il intima au démon de transporter, jarres et lui-même, immédiatement chez lui. Le brahma-rakshasa s’exécuta et le barbier fut transporté chez lui avec tout le trésor. Le démon le supplia alors de le libérer, mais le barbier n’avait aucune envie de se priver de ses services si tôt. Aussi lui demanda-t-il de couper le riz de son champ et de ramener la récolte chez lui. Le malheureux démon, se croyant toujours dans les griffes du barbier, consentit à lui moissonner sa récolte. |

| As he was cutting the paddy, a brother demon happened to pass that way. He asked the brahmarakshasa what he was doing. The first demon told him how he had accidentally fallen into the hands of a shrewd man and had no way of escaping his clutches unless he did what he was told. So he was reaping the man’s rice crop. The second demon laughed and said, “Have you gone mad, my friend? We demons are superior to men and much more powerful. How can any man have any power over us? Can you show me the house of this man?” | Comme il coupait le riz, un de ses frères démons vint à passer par là. Il demanda au brahma-rakshasa ce qu’il était en train de faire. Le premier démon lui raconta comment il était tombé par accident entre les pattes d’un homme rusé, et n’avait aucun moyen d’échapper à ces griffes s’il ne s’exécutait pas. Il était donc en train de moissonner le riz de cet homme. Le second démon s’esclaffa et lui demanda : « Es-tu devenu fou, mon ami ? Nous autres démons, sommes supérieurs aux hommes et bien plus puissants. Comment un vulgaire être humain peut-il avoir un quelconque pouvoir sur nous ? Peux-tu m’indiquer la maison de cet homme ? » |

| “I can,” replied the first demon, “but only from a distance. I dare not go near it till I’ve cut all this paddy.” Then he showed him the way to the barber’s house. | « Oui, mais seulement de loin », répondit le premier démon. Je n’ose m’approcher avant d’avoir moissonné toute sa récolte. Puis il lui indiqua le chemin du logis du barbier. |

| Meanwhile, the barber was celebrating his newfound wealth. He had bought a big fish for the party, but unfortunately a cat had entered the kitchen through a broken window and had eaten up most of it. The barber’s wife was very angry and wanted to kill the animal. When she went after it, the cat escaped through the same window by which it had entered. Knowing the ways of cats, she expected it to return, so she stood there waiting with a fish knife in her hand. Now the second brahmarakshasa tiptoed like a thief towards the house and wanted to take a peek at his friend’s captor. So he slowly thrust his bushy head through the broken window. The angry wife, who was waiting there for the naughty cat, brought down her sharp knife on the intruding demon and made a clean slash through his long nose, cutting off the tip. In pain and fright, the demon ran away, ashamed of showing his friend a face minus a nose. | Pendant ce temps, le barbier célébrait sa toute nouvelle richesse. Il avait apporté un énorme poisson pour la fête, mais malheureusement, par une vitre cassée, un chat s’était introduit dans la cuisine et l’avait englouti presque tout entier. La femme du barbier, furibarde, voulut le tuer. Mais au moment de l’attraper, le chat s’échappa par la vitre par laquelle il était entré. Connaissant les habitudes des félins, elle attendit son retour, armée d’un couteau à poisson. C’est à ce moment-là que le second brahma-rakshasa, sur la pointe des pieds, tel un voleur, s’approcha de la maison, désirant jeter un coup d’œil au ravisseur de son ami. Aussi, doucement, s’introduisit-il, tout ébouriffé, par la vitre brisée. L’épouse, à l’affût du méchant chat, abattit son couteau acéré sur l’intrus, causant une balafre à son long nez, dont le bout fut coupé net. Fou de douleur et de peur, le démon s’enfuit, honteux de présenter à son ami un visage amputé de son nez. |

| The first demon patiently reaped all the grain and came back to the barber for his release. The wily barber showed him the back of the mirror. The brahmarakshasa looked at it anxiously and was relieved not to find his image in it. So he fetched a deep sigh and went his way, dancing with a light heart. | Entre temps, le premier démon avait patiemment moissonné la récolte toute entière et il retourna chez le barbier, espérant être enfin libéré. Rusé comme un renard, celui-ci lui tendit le dos du miroir. Anxieux, le brahma-rakshasa le regarda et fut soulagé de ne plus y voir son reflet. Il poussa alors un profond soupir et, le cœur léger, reprit sa route en dansant. |

| 1 | Le nom actuel de cette ville au nord-ouest de Calcutta est Bardhaman. |

| 2 | Le brahmarākṣasaḥ (ब्रह्मराक्षसः) est une créature de la mythologie hindoue proche du vampire européen, et qui s’attaque aux humains pour leur sucer le sang. Originellement, ce sont des fantômes de brahmanes. Plus de détails (en anglais) sur  . . |

| If God is everywhere | Si Dieu est partout |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| A sage had a number of disciples. He taught them his deepest belief: “God is everywhere and dwells in everything. So you should treat all things as God and bow before them.” | Un sage avait de nombreux disciples. Il leur enseignait sa plus intime conviction : « Dieu est partout et habite en toute chose. Aussi devriez-vous traiter toutes choses comme étant Dieu et vous prosterner devant elles. » |

| One day when a disciple was out on errands, a mad elephant was rushing through the marketplace, and the elephant driver was shouting, “Get out of the way! Get out of the way! This is a mad elephant!” The disciple remembered his guru’s teachings and refused to run. “God is in this elephant as He is in me. How can God hurt God?” he thought, and just stood there full of love and devotion. The driver was frantic and shouted at him, “Get out of the way! You’ll be hurt!” But the disciple did not move an inch. The mad elephant picked him up with his trunk, swung him around, and threw him in the gutter. | Un jour, alors qu’un disciple était sorti faire ses emplettes, un éléphant hors de contrôle déboula sur la place du marché ; son cornac criait : « Dégagez, dégagez ! Cet éléphant est fou ! » Le disciple se souvint des enseignements de son gourou et refusa de courir. « Dieu est dans cet éléphant, tout comme il est en moi. Comment Dieu peut-il blesser Dieu ? » pensa-t-il, et il resta planté là, rempli d’amour et de dévotion. Le cornac était hors de lui et criait : « Écarte-toi ! Tu vas être blessé ! » Mais le disciple ne bougea pas d’un millimètre. L’éléphant l’attrapa avec sa trompe, le fit virevolter dans les airs et le projeta dans le caniveau. |

| The poor fellow lay there, bruised, bleeding, but more than all, disillusioned that God should do this to him. When his guru and the other disciples came to help him and take him home, he said, “You said God is in everything! Look what the elephant did to me!” | Le pauvre garçon gisait là, contusionné, saignant, mais avant tout désabusé que Dieu ait pu le malmener ainsi. Quand son gourou, accompagné des autres disciples, vint à son secours et le ramena chez lui, il lui dit : « Vous avez dit que Dieu est dans toute chose ! Regarde ce que cet éléphant m’a fait ! » |

| The guru said, “It’s true that God is in everything. The elephant is certainly God. But so was the elephant driver, telling you to get out of the way. Why didn’t you listen to him?” | Le gourou répondit : « En effet, Dieu est en tout. Cet éléphant est certainement Dieu. Mais le cornac aussi, qui t’a dit de t’écarter du chemin. Pourquoi ne pas l’avoir écouté ? » |

| Untold stories | Histoires jamais racontées |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| A Gond peasant kept a farmhand who worked for him in the fields. One day they went together to a distant village to visit the Gond’s son and his wife. On the way they stopped at a little hut by the roadside. After they had eaten their supper, the farmhand said, “Tell me a story.” But the Gond was tired and went to sleep. His servant lay awake. He knew that his master had four stories, which he was too lazy to tell. | Un paysan Gond employait un valet de ferme qui l’aidait dans les champs. Un jour, ils allèrent ensemble dans un village éloigné rendre visite au fils du fermier et à sa femme. En chemin, ils s’arrêtèrent dans une petite cabane au bord de la route. Après avoir dîné, l’ouvrier dit à son maître : « Racontez-moi une histoire. » Mais le Gond était fatigué et s’endormit. Son serviteur, lui, resta éveillé. Il savait que son maître connaissait quatre histoires, mais qu’il était trop paresseux pour les raconter. |

| When the Gond was fast asleep, the stories came out of his belly, sat on his body, and began to talk to each other. They were angry. “This Gond”, they said, “knows us very well from childhood, but he will never tell anybody about us. Why should we go on living uselessly in his belly? Let’s kill him and go to live with someone else.” The farmhand pretended to be asleep, but he listened carefully to everything they said. | Quand le Gond fut profondément endormi, les histoires jaillirent de son ventre et commencèrent à bavarder entre elles. Elles étaient furieuses : « Depuis qu’il est enfant, ce Gond nous connaît par cœur, mais il ne nous racontera jamais à qui que ce soit. Pourquoi devrions-nous continuer à vivre inutilement dans son ventre ? Tuons-le et allons vivre chez quelqu’un d’autre. » Le valet faisait semblant de dormir, mais il ne perdit pas une miette de ce qu’elles racontaient. |

| The first story said, “When the Gond reaches his son’s house and sits down to eat his supper, I’ll turn his first mouthful of food into sharp needles, and when he swallows them, they’ll kill him.” | La première histoire dit : « Quand le Gond arrivera chez son fils et s’assoira pour dîner, je transformerai sa première bouchée de nourriture en aiguilles pointues, et quand il les avalera, elles le tueront. » |

| The second story said, “If he escapes that, I’ll become a great tree by the roadside. I’ll fall on him as he passes by and kill him that way.” | La seconde histoire renchérit : « S’il en réchappe, je me transformerai en un arbre immense arbre au bord de la route. Je tomberai sur lui au moment où il passera et le tuerai ainsi. » |

| The third story said, “If that doesn’t work, I’ll be a snake and run up his leg and bite him.” | La troisième histoire proposa alors : « Si tout cela ne marche pas, je deviendrai un serpent, m’enroulerai autour de sa jambe et le mordrai. » |

| The fourth said, “If that doesn’t work, I’ll bring a great wave of water as he is crossing the river and wash him away.” | La quatrième conclut : « Et si malgré tout cela il est encore vivant, je provoquerai une grosse vague au moment où il traversera la rivière et je l’emporterai. » |

| The next morning the Gond and his servant reached his son’s house. His son and daughter-in-law welcomed him and prepared food and set it before him. But as the Gond raised his first mouthful to his lips, his servant knocked it out of his hand, saying, “There’s an insect in the food.” When they looked, they saw that all the rice had turned into needles. | Le lendemain matin, le Gond et son serviteur atteignirent la demeure de son fils. Celui-ci et sa belle-fille l’accueillirent, lui préparèrent un repas qu’ils déposèrent devant lui. Mais au moment où le Gond portait la première bouchée à ses lèvres, son valet la fit tomber d’un coup sec en disant : « Il y a un insecte dedans. » Quand ils regardèrent, ils virent que tout le riz s’était transformé en aiguilles. |

| The next day the Gond and his servant set out on their return journey. There was a great tree leaning across the road, and the servant said, “Let’s run past that tree.” As they ran past it, the tree fell with a mighty crash, and they just escaped. A little later, they saw a snake by the road, and the servant quickly killed it with his stick. After that they came to the river and as they were crossing, a great wave came rushing down, but the servant dragged the Gond to safety. | Le lendemain, le Gond et son valet prirent le chemin du retour. Un grand arbre penché se dressait au-dessus de la route, et le serviteur dit : « Passons dessous au pas de course. » À peine passés, l’arbre s’écroula dans un fracas épouvantable : ils l’avaient échappé belle ! Un peu plus tard, ils aperçurent un serpent au bord de la route, que le valet tua d’un habile coup de bâton. Ils arrivèrent ensuite près de la rivière et alors qu’ils la traversaient, une grosse vague déferla, mais le serviteur mit son maître à l’abri. |

| They sat down on the bank to rest, and the Gond said, “You have saved my life four times. You know something I don’t. How did you know what was going to happen?”’ The farmhand said, “If I tell you I’ll turn into a stone.” The Gond said, “How can a man turn into a stone? Come on, tell me.” So the servant said, “Very well, I’ll tell you. But when I turn into a stone, take your daughter-in-law’s child and throw it against me, and I’ll become a man again.” | Ils s’assirent sur la berge pour se reposer, et le fermier déclara : « Tu m’as sauvé la vie quatre fois. Tu sais des choses que j’ignore. Comment as-tu su ce qui allait se passer ? » L’ouvrier répondit : « Si je vous le dis, je serai transformé en pierre. » Le Gond demanda : « Comment un homme peut-il se devenir une pierre ? Allez, raconte ! » Alors le serviteur répondit : « Très bien, je vais vous le dire. Mais quand je serai devenu pierre, prenez l’enfant de votre belle-fille et lancez-le contre moi ; alors je redeviendrai un homme. » |

| So the servant told his story and was turned into a stone, but the Gond left him there and went home. After some time, his daughter-in-law heard about it, and she went all by herself and threw her child against the stone, and the servant came to life again. | Alors le valet raconta l’histoire et il fut transformé en pierre, mais le Gond le laissa là et rentra chez lui. Quelque temps après, cette histoire parvint jusqu’aux oreilles de sa belle-fille, et de sa propre initiative, elle précipita son enfant contre la pierre, et le serviteur revint à la vie. |

| But the Gond refused to have him in his house and dismissed him. That’s why few people in this region trust a Gond. They even have a saying: “No one can rely on a Gond, a woman, or a dream.” | Mais le Gond ne voulut plus de ses services et le congédia. Voilà pourquoi peu de gens dans cette région font confiance à un Gond. Ils ont même un dicton : « On ne peut se fier à un Gond, ni à une femme ni à un rêve. » |

| A crow’s revenge | La revanche du corbeau |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| In the branches of a big banyan tree, a crow family built a nest and lived in it. A black snake would crawl through its hollow trunk and eat the crow chicks as soon as they were hatched. After this had happened many times, the crow wife couldn’t take it any longer. She said to the crow, “We’ve lost all our chicks to this awful snake, who just waits for me to hatch them and gobbles them all up. We are utterly helpless. Let’s move out of this tree.” But the crow liked the tree, had grown used to it, and he said, “We must find a way to kill this enemy of ours.” | Au creux des branches d’un grand banyan, une famille corbeau avait bâti un nid et vivait là. Un serpent noir avait l’habitude de ramper à travers son tronc creux pour dévorer les corbillats tout juste éclos. Ceci s’étant répété de nombreuses fois, la femelle du corbeau ne put le supporter davantage. Elle dit au corbeau : « Nous avons abandonné tous nos corbillats à cet épouvantable serpent qui n’attend qu’une chose : que je les couve pour les gober. Nous sommes totalement impuissants. Quittons cet arbre. » Mais le corbeau aimait cet arbre, y avait ses habitudes et répondit : « Il faut que nous trouvions un moyen de tuer notre ennemi commun. » |

| “How can we? We are mere crows. He is such a big snake.” “There must be ways. I may be small and weak, but I’ have cunning friends. This time, I’ll not let this pass.” | « Mais comment ? Nous ne sommes que de simples corbeaux. C’est un si gros serpent ! Il doit bien avoir un quelconque moyen de s’en débarrasser. Je suis petit et faible mais j’ai des amis rusés. Cette fois, ça ne se passera pas comme ça ! ». |

| So he went to his friend the jackal, who heard his case and advised him: We’ll take care of this villain. Go to that lake, where the king and his queens bathe and swim. Pick up a necklace or a jewel, fly away with it, and put it in the snake’s hole.” | Aussi alla-t-il voir son ami le chacal, qui écouta son histoire et lui proposa : « Nous allons régler son compte à ce scélérat. Rends-toi à ce lac où le roi et les reines se baignent et nagent. Vole un collier ou un bijou, enfuis-toi avec et dépose-le dans la cache du serpent. » |

| The crow at once flew off to the lake and waited for the king’s party to arrive, undress, take off their gold chains and pearl necklaces, and get into the water. Then when they were busy enjoying themselves, he picked up a necklace and flew away. The king’s servants saw this, and quickly picked up their spears and sticks and pursued the crow. | Sur le champ, le corbeau s’envola vers le lac et attendit que la cour du roi arrive, se dévête, retire chaînes en or et autres colliers de perles et pénètre dans l’eau. Puis, quand ils furent occupés à s’amuser, il déroba un collier et s’enfuit. Les serviteurs du roi, témoins de la scène, se saisirent promptement de lances et de bâtons et partirent à la poursuite du corbeau. |

| The crow went straight to the snake’s hole under the tree and dropped the necklace in it. The king’s servants dug up the hole, found the black snake, beat it to death, picked up their queen’s necklace, and went their way. | Celui-ci se dirigea immédiatement vers le terrier du serpent, sous l’arbre, et y laissa tomber le collier. Les serviteurs du roi creusèrent ce trou, découvrirent le serpent noir, le battirent à mort, récupérèrent le collier de la reine et allèrent leur chemin. |

| The crow and his family were left in peace. | Ils laissèrent le corbeau et sa famille en paix. |

| Tell It to the Walls | Dis-le aux murs ! |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| A poor widow lived with her two sons and two daughters-in-law. All four of them scolded and ill-treated her all day. She had no one to whom she could turn and tell her woes. As she kept all her woes to herself, she grew fatter and fatter. Her sons and daughters-in-law now found that a matter for ridicule. They mocked at her for growing fatter by the day and asked her to eat less. | Une pauvre veuve vivait avec ses deux fils et ses deux belles-filles. Tous les quatre la réprimandaient et la maltraitaient toute la journée. Elle n’avait personne vers qui se tourner pour raconter ses malheurs. Comme elle gardait toutes ses contrariétés pour elle, elle grossissait. Ses fils et ses belles-filles en avaient fait un sujet de raillerie. Ils se moquaient sans cesse de son embonpoint croissant et lui demandaient de manger moins. |

| One day, when everyone in the house had gone out somewhere, she wandered away from home in sheer misery and found herself walking outside town. There she saw a deserted old house. It was in ruins and had no roof. She went in and suddenly felt lonelier and more miserable than ever; she found she couldn’t bear to keep her miseries herself any longer. She had to tell someone. | Un jour, alors que tous étaient sortis, elle erra loin de la maison, en proie à une profonde détresse et se retrouva hors de la ville. Là, elle vit une masure abandonnée, en ruines, sans toit. Elle y pénétra et se sentit soudain plus seule et plus malheureuse que jamais ; elle réalisa qu’elle ne pouvait plus supporter de garder ses malheurs par devers elle. Il lui fallait les raconter à quelqu’un. |

| So she told all her tales of grievance against her first son to the wall in front of her. As she finished, the wall collapsed under the weight of her woes and crashed to the ground in a heap. Her body grew lighter as well. | Alors fit-elle le récit de ses tous ses griefs à l’encontre de son fils aîné au mur face à elle. Comme elle terminait son récit, le mur s’effondra sous le poids de ses souffrances et forma un amas sur le sol. Son corps s’allégea d’autant. |

| Then she turned to the second wall and told it all her grievances against her first son’s wife. Down came that wall, and she grew lighter still. She brought down the third wall with her tales against her second son, and the remaining fourth wall, too, with her complaints against her second daughter-in-law. | Puis elle se tourna vers le second mur et lui raconta tous ses griefs à l’encontre de la femme de son fils aîné. Ce mur-là s’écroula aussi, et elle s’allégea encore. Elle fit crouler le troisième mur en racontant les misères infligées par son fils cadet, et le quatrième, encore debout, s’effondra après avoir entendu les griefs à l’encontre de sa deuxième bru. |

| Standing in the ruins, with bricks and rubble all around her, she felt lighter in mood and lighter in body as well. She looked at herself and found she had actually lost all the weight she had gained in her wretchedness. | Debout au milieu des ruines, entourée de décombres, elle se sentait plus légère, tant d’esprit que de corps. Elle se regarda et constata qu’elle avait bel et bien perdu tous les kilos que le malheur lui avait fait prendre. |

| Then she went home. | Ainsi délivrée, elle rentra chez elle. |

| The Jasmin Prince | Le Prince Jasmin |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| There was once a king who was called the Jasmine Prince because the scent of jasmines would waft from him for miles whenever he laughed. But for that to happen, he had to laugh naturally, all by himself. If someone else tickled him or forced him to laugh, there would be no scent of jasmines. | Il était une fois un roi que l’on appelait le Prince Jasmin car, chaque fois qu’il riait, il exhalait un magnifique parfum qui embaumait à des lieues à la ronde. Mais cela ne pouvait se produire que par un rire naturel, spontané. Par exemple, si quelqu’un le chatouillait ou le forçait à rire, rien, aucune senteur ! |

| The Jasmine Prince ruled a small kingdom and paid tribute to a king greater than himself, who had heard of this extraordinary power to produce the scent of jasmines by merely laughing. The great king wanted to see how it happened and to experience it himself, so he invited the Jasmine Prince to his court and asked him to laugh. But the prince couldn’t laugh to order. He tried and tried, but he just couldn’t bring himself to laugh. The great king was furious. “He is defying orders. He is trying to insult us”, he thought, and clapped him in jail till he produced some laughter. | Le Prince Jasmin régnait sur un petit territoire qui dépendait d’un un royaume plus grand. Son roi, qui avait entendu parler de cet extraordinaire pouvoir d’exhaler une fragrance de jasmin rien qu’en riant, voulut voir ce prodige de ses propres yeux et l’expérimenter lui-même. Aussi invita-t-il le Prince Jasmin à sa cour et lui demanda-t-il de rire tout simplement. Mais, comme nous l’avons vu, le prince ne pouvait pas rire sur commande ! Maintes fois, il essaya, mais aucune raison ne l’incitait à rire spontanément. Le roi se mit alors en colère. « Il défie mes ordres. Il me couvre de ridicule ! », pensa-t-il, et il incarcéra le malheureux prince jusqu’à ce que celui-ci puisse émettre son rire parfumé. |

| Right in front of the prison house lived a cripple in a hut. The queen of the realm had fallen in love with this cripple and would visit him at night. From his window, the Jasmine Prince watched her come and go. “But that’s not my business”, he thought, and behaved as if he had seen nothing. One night, the queen was late. The cripple was furious when she arrived at last, and he beat her up. He pounded her with his arm-stumps and kicked her with his lame leg. The queen patiently endured all this battering and didn’t say a thing. She took out the royal dishes that she had brought for him and lovingly served him. After a while the cripple, regretting his brutal treatment of the queen, asked softly, “Aren’t you angry that I beat you up?” she replied, “Oh no! It was delightful. I felt great, as if I had seen all fourteen worlds at once!” | Face à la prison vivait dans une hutte un infirme boiteux. La reine du royaume était tombée amoureuse de ce pauvre hère et avait l’habitude de lui rendre visite à la nuit tombée. De sa fenêtre, le Prince Jasmin la voyait arriver il scrutait ce ballet. « Mais cela ne me regarde pas », pensa-t-il, et il fit comme s’il n’avait rien vu. Un soir, la reine étant arrivée en retard, l’infirme, furieux, la roua de coups lorsqu’elle le rejoignit enfin. Il l’entrava avec ses moignons et lui lança maints coups de pied avec sa jambe estropiée. La reine endura patiemment tous ces coups sans mot dire. Puis elle sortit les mets royaux qu’elle lui avait apportés et le servit avec amour. Quelques instants plus tard, l’infirme, regrettant sa conduite brutale envers la reine, lui demanda doucement : « N’es-tu pas en colère contre moi pour t’avoir ainsi frappée ? » Elle répondit : « Oh non, c’était délicieux ! J’avais l’impression d’embrasser les quatorze mondes d’un coup ! » |

| Now, right next to the veranda where they were talking to each other, a poor washerman was cowering in a corner in the cold. He had lost his donkey and had searched for it in vain for four or five days. He had despaired of ever finding the animal. But when he heard the queen say what she did, he thought, “If this lady has seen all fourteen worlds, surely she will have seen my donkey somewhere.” So he called out to her, “Lady, did you see my donkey anywhere?” At this the Jasmine Prince, who had been listening from his window, could not keep from laughing. He let out peal after peal of laughter into the night, and at once the air for miles around was filled with the fragrance of jasmines. The dawn was still some hours away, but the prison guards ran to the great king and told him of the laughter and the burst of fragrance. Without even waiting for dawn, the king had the Jasmine Prince brought to his palace and said to him, “When I asked you to laugh for me the other day, you couldn’t. But now, what on earth made you laugh in the middle of the night?” | Tout près de la masure où ils devisaient, un pauvre blanchisseur était recroquevillé à l’angle de la rue, transi de froid. Son âne l’avait quitté et il le cherchait en vain depuis quatre ou cinq jours. Il avait perdu tout espoir de jamais retrouver l’animal. Mais quand il entendit la reine raconter ce qu’elle avait ressenti, il pensa : « Si elle a vu les quatorze mondes, elle a sûrement vu mon âne quelque part… » Aussi lui demanda-t-il respectueusement : « Ma chère dame, avez-vous vu mon âne quelque part ? » Le Prince Jasmin, qui avait été témoin depuis la fenêtre de sa cellule, ne put s’empêcher d’éclater de rire. Il laissa échapper un carillon d’éclats de rire dans la nuit, et aussitôt, l’air, à des lieues à la ronde, se remplit de la fragrance de jasmins. Bien que l’aube fût encore loin, les gardiens de prison se précipitèrent chez le roi pour lui faire part de ces éclats de rire et de l’exhalaison de la senteur suave qui en résultait. Aussitôt dans la nuit, le roi envoya quérir le Prince Jasmin pour le ramener au palais et lui dit : « Tu fus incapable de rire pour me satisfaire lorsque je te l’ai demandé l’autre jour. Alors qu’est-ce qui a bien pu te faire rire au beau milieu de la nuit ? » |

| The prince tried hard to hold back the reason for his laughter, but the king insisted, so the prince told him the truth. When the king had heard everything, he issued two orders. One was to send the Jasmine Prince back to his capital with all due honours. The other was to throw his queen at once into the limekiln. | Le prince s’efforça de ne pas dévoiler la raison de son rire, mais le roi insista tant que le prince finit par lui avouer la vérité. Après l’avoir écouté, le roi intima deux ordres : raccompagner le Prince Jasmin dans sa capitale avec tous les honneurs dus à son rang et… jeter sur-le-champ la reine dans le four à chaux ! |

| The Clay Mother-in-Law | La belle-mère d’argile |

|---|---|

| Attipate K. Ramanujan | Traduction : Francine de Perczynski |

| Once upon a time, there was a very docile daughter-in-law. She was obedient to her husband’s mother and waited upon her slightest wish. The old woman kept up her dignity as a mother-in-law, saying very little and often merely nodding her commands. Every morning, the daughter-in-law would come to the old woman and ask her how many measures of rice she should cook for that day. The old woman would ponder the problem seriously and then hold up her hand. On some days the hand would show two outstretched fingers, on other days it would show three, according to her fancy. The daughter-in-law would take the order silently and go into the kitchen to cook two measures of rice, or three, as the wrinkled hand commanded. | Il était une fois une belle-fille d’une extrême docilité. Elle obéissait à la mère de son mari et était aux petits soins pour elle. La vieille femme, avare en paroles, portait haut sa dignité de belle-mère et ordonnait d’un simple mouvement de tête. Chaque matin, la belle-fille venait voir la vieille femme et lui demandait combien de mesures de riz elle devait cuisiner ce jour-là. La vieille femme réfléchissait sérieusement au problème et levait la main, deux doigts tendus, d’autres jours trois, selon sa fantaisie. La belle-fille prenait la commande sans broncher et allait dans la cuisine silencieusement y préparer deux mesures de riz, ou trois, selon ce que la main ridée lui avait ordonné. |

| One day the old woman fell ill and passed away. The young daughter-in-law wept her eyes out. She could not see her way about the little house, and she missed her mother-in-law’s daily instructions. Who was there now to tell her how much she should cook for the day? She was in a perpetual funk, unable to make any decisions. Her husband was at first pleased with his wife’s devotion to his mother, but he soon tired of answering her eternal questions about measures of rice. | Un jour, la vieille femme tomba malade et mourut. La jeune belle-fille pleura à chaudes larmes. Elle errait sans but dans la petite maison et les consignes quotidiennes de sa belle-mère lui manquaient. Qui allait lui indiquer désormais quelle quantité de riz cuisiner pour la journée ? Incapable de prendre la moindre décision, elle était sans cesse désemparée. Au début, la dévotion de sa femme envers sa mère avait réjoui son mari, mais il fut bientôt excédé de devoir répondre à ses sempiternelles questions sur les mesures de riz. |

| He thought of a way out of all this bother. He went to the nearest potter and ordered a clay image of his mother, as large as life. He gave special instructions to the potter to make one hand show two fingers and the other three. In a few days the clay mother-in-law was painted, dressed, and ready for use. The husband brought it home and planted it in a prominent place near the kitchen. The young wife was delighted at the return of her lost mother-in-law. It seemed to be the end of her troubles, and she could begin the day properly now. Whenever she was in doubt about measures of rice, she would look out of the kitchen and take orders. If she happened to see the two-fingered hand first, she would cook two measures for the day; if she caught a glimpse of the three-fingered hand, that day the rice-pot would overflow with boiled rice. She was happy with the clay mother-in-law, and her husband was happy with the happiness of his wife. | Il chercha un moyen de sortir de tout ce tracas. Il se rendit chez le potier le plus proche et lui commanda une effigie en argile de sa mère, grandeur nature. Il donna des instructions spéciales au potier pour qu’une main montre deux doigts et l’autre trois. En l’espace de quelques jours, la belle-mère en argile fut peinte, vêtue et prête à l’emploi. Le mari la rapporta à la maison et la planta dans un endroit bien en évidence près de la cuisine. La jeune épouse fut enchantée du retour de sa belle-mère disparue. Il semblait que c’était la fin de ses ennuis, et dès lors elle pouvait bien démarrer la journée. Chaque fois qu’elle doutait des mesures de riz, elle jetait un coup d’œil hors de la cuisine et recevait ses ordres. Si elle voyait la main à deux doigts en premier, elle cuisinait deux mesures pour la journée ; si c’était la main à trois doigts, la marmite de riz débordait de riz cuit ce jour-là. Elle était heureuse avec la belle-mère d’argile, et son mari, heureux du bonheur de sa femme. |

| Things went on smoothly for a while, till one day the husband became aware that his rice-bags were being emptied every few weeks, though there were only two people in the house. He asked his wife, and she told him her daily procedure: she asked her mother-in-law every morning and followed her instructions. Her husband was furious: “Two or three measures of rice every day for just the two of us? Ridiculous! We aren’t eating all of it, are we? When my mother was alive, you used to cook the same two measures and all three of us would have our bellies bursting!” She replied in a low voice, “We are not two, but three. You’ve forgotten Mother. As usual, I give her dinner before I eat. On many days, I’ve very little left for myself. If you don’t mind my saying so, Mother eats more rice than she used to.” | Tout alla bien pendant quelque temps jusqu’au jour où le mari s’aperçut que les sacs de riz se vidaient à vue d’œil bien qu’ils ne fussent que deux à la maison. Il interrogea sa femme qui lui décrivit sa routine : elle questionnait sa belle-mère tous les matins et suivait ses instructions. Son mari s’emporta : « Deux ou trois mesures de riz par jour pour nous deux ? Ridicule ! Nous n’en avons pas besoin d’autant, n’est-ce pas ? Quand ma mère était encore en vie, tu cuisinais les deux mêmes mesures et on avait tous les trois le ventre plein à craquer ! » Elle répondit à voix basse : « Nous ne sommes pas deux, mais trois. Tu oublies Mère. Comme d’habitude, je lui sers son dîner avant de manger moi-même. Souvent, il ne me reste pas grand-chose. Si je peux m’exprimer ainsi, Mère mange plus de riz qu’avant. » |

| The husband couldn’t believe his ears. What was this wild tale of a mud mother-in-law eating up whole bags of rice? He flew into a rage and beat up his wife. Then he threw her out, and her clay mother-in-law with her. | Le mari n’en croyait pas ses oreilles. Qu’est-ce que c’était que cette histoire dingue d’une belle-mère d’argile dévorant des sacs entiers de riz ? Fou de rage, il étrilla sa femme. Puis il la jeta dehors, et sa belle-mère d’argile avec elle. |

| But the truth was this: twice every day, the young wife, according to custom, would spread a leaf before her mother-in-law and serve all the dishes one by one. But as soon as she went into the kitchen, the neighbour’s wife would come in quietly through a cunningly made hole in the wall, steal all the food, and vanish the way she came. This way, she didn’t have to cook at all. The poor fool of a daughter-in-law believed all along that her mother-in-law had dined off her leaf as usual. Her innocence had now landed her in the streets. | Mais en vérité, deux fois par jour, la jeune épouse, selon la coutume, étalait une feuille devant sa belle-mère et lui servait tous les plats un par un. Mais à peine était-elle de retour dans la cuisine que la femme du voisin, se glissant subrepticement par un trou pratiqué dans le mur, dérobait toute la nourriture pour disparaître par le même chemin. Ainsi était-elle dispensée de cuisiner ! La belle-fille, simplette, continuait de croire que sa belle-mère consommait son repas, comme d’habitude. Sa naïveté l’avait maintenant conduite jusque dans la rue. |

| She was miserable. She took the effigy of her beloved mother-in-law in her arms and walked into the night, afraid of the dark, crying, praying, cursing her fate. She walked and walked and soon came to the woods outside the town. She clutched her mother-in-law closer to her bosom and shivered in the terrifying dark. Every little sound scared the poor young woman, who had rarely before stepped out of her house. She somehow climbed a tree and tied herself to a branch with her sari, clinging all the while to her mother-in-law. As she sat there trembling, she heard loud footfalls. Burly moustached men, with burning torches in their hands, were parting the bushes and coming towards her tree. From their dress and their murderous looks, she guessed they were thieves. They came right under the tree where she was hiding. Tired after a busy day, they lowered their burdens from their backs and sat down to share the loot. In the light of the torches, they seemed like devils to her. The poor woman began to shake with fear and lost her grip on the clay mother-in-law. Down it fell, with a great big crash, right on the gang of thieves under the tree. | Elle était bien malheureuse. Elle prit l’effigie de sa belle-mère adorée dans ses bras et s’enfonça dans la nuit, effrayée par l’obscurité, pleurant, priant, maudissant son destin. Elle déambula et arriva bientôt à la lisière de la forêt, près de la ville. Elle étreignit sa belle-mère sur sa poitrine et se mit à trembler dans ces ténèbres terrifiantes. Le moindre bruit apeurait la pauvre jeune femme, qui n’avait que rarement quitté son logis. Elle réussit à grimper dans un arbre, s’attacha à une branche avec son sari, tout en agrippant sa belle-mère. Alors qu’elle se tenait là, tremblante, elle entendit de lourds bruits de pas. Des gaillards moustachus, une torche allumée à la main, écartaient les buissons et s’approchaient de son arbre. Au vu de leur accoutrement et de leurs mines patibulaires, elle devina qu’ils étaient des brigands. Ils se mirent juste sous l’arbre où elle se cachait. Fourbus après une journée bien remplie, ils se délestèrent de leurs fardeaux et s’assirent pour partager le butin. À la lueur des torches, ils lui semblaient des diables. La pauvre femme se mit à trembler de peur et lâcha la belle-mère d’argile. Avec un grand fracas, elle dégringola pour atterrir au beau milieu du gang des voleurs sous l’arbre. |

| The thieves panicked and took to their heels, and fled in all directions before they knew what had hit them. Meanwhile the young wife had fainted from sheer terror, and she lay unconscious among the branches till dawn. | Paniqués, les larrons prirent leurs jambes à leur cou et s’enfuirent dans toutes les directions sans comprendre ce qui les avait frappés. Entre-temps, la jeune femme s’était évanouie d’effroi, et gît, inconsciente, jusqu’à l’aube, au beau milieu des branches. |

| When day dawned and she woke up as from a nightmare, the first thing she saw on the forest floor was her clay mother-in-law, broken in three pieces, surrounded by countless treasures and a few burnt-out torches. After making sure there was no one around, she carefully climbed down from her perch and gathered up the pieces of her clay mother-in-law. She thanked her for saving her life and for bringing her an undreamed-of treasure. | Quand le jour se leva et qu’elle émergea de ce cauchemar, la première chose qu’elle vit sur le sol forestier fut sa belle-mère d’argile, brisée en trois morceaux, entourée d’innombrables trésors et de quelques torches consumées. Après s’être assurée qu’il n’y avait personne alentour, elle descendit avec précaution de son perchoir et rassembla les morceaux de sa belle-mère d’argile. Elle la remercia de lui avoir sauvé la vie et de lui avoir apporté un trésor inespéré. |